Heterophonics (Sound Performance, 1976)

Creator:

Marshall, StuartContributor(s):

-

Nick Collins, Jane Harrison

-

Year: 1976

Type of work:Performance

First exhibited: 2B Butler;s Wharf, London

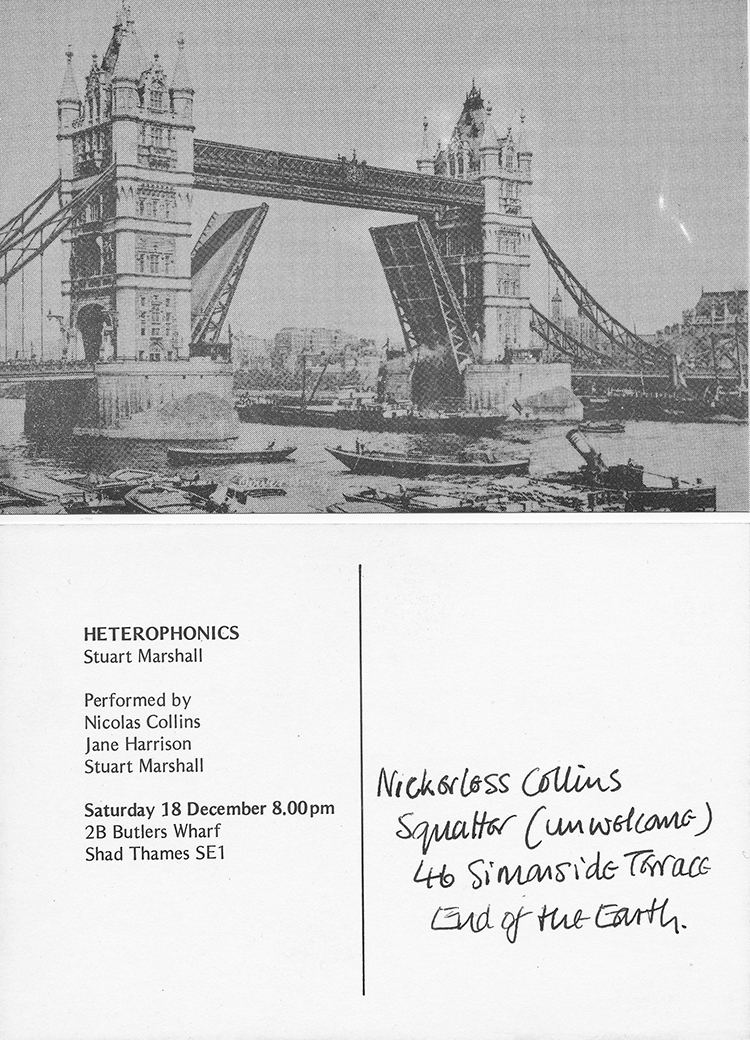

Sound performance at 2b Butler’s Wharf in London, December 18, 1976. Performed by Nick Collins, Jane Harrison, and Stuart Marshall.

Wood striking wood, quick, hard, BOK! Impact sound sprays out, an omni-directional striking of all reflective surfaces and returning through time to the distributed centres of listening, the BOK-space of audition. This is the basis of Stuart Marshall’s composition known as Idiophonics or Heterophonics, a piece performed only occasionally in the 1970s and now about to be revived.

I was present at a 1976 performance that began in 2B, Butlers Wharf, then spread out along the Thames and over Tower Bridge. Memories of the event are foggy (that may also have been true for the winter weather) but I wrote a contemporaneous account in Readings magazine (edited by Annabel Nicolson and Paul Burwell, 1977). In that essay I described Stuart’s work with sound as being “fairly unique in this country”. Of course he could be unique or not unique, not “fairly unique”; what I was trying to convey was an emergence of sound work, an engagement parallel to contemporary art practices such as structural film and video with their intellectual preoccupations (notably Lacan) that rejected the rituals of music. As an approach it was rare though not unknown.

The piece began with three people – Stuart Marshall, Jane Harrison and Nicolas Collins – striking closely-pitched woodblocks, moving away from each other every time their strikes coincided. In a second phase they took up aerosol klaxons (“used in America for scaring off intruders and bears”, as I wrote in the Readings essay) and moved out into the freezing night: “One of the players stayed close to the building, one moved along the river to the right and the third walked out over Tower Bridge. The sounds bounced back and forth in a most spectacular way for quite some time – after a little while most of the audience left the rather precarious platforms which jut from the doors and huddled around an electric fire. Conversations started up and the piece took on the dimensions of a social gathering punctuated by alternately mournful and strident honking from outside.”

David Cunningham was present – his photograph of a murky Tower Bridge was used to illustrate my writing. Nearly 40 years later he recalls as little as me. “I remember talking to Gavin Bryars,” he tells me in an email, “as the ship approached Tower Bridge which remained closed until the last possible minute. There was a possibility that the klaxons were confusing whatever signalling system the bridge uses and some speculation about another maritime disaster for Gavin to turn into a score. I have a feeling the ship sounded a klaxon too.”

Within these accounts there are indications of a new way to be within the experience of a sound work. Nothing of the event could be conveyed through secondary media – you had to be there – but to behave as a conventional ‘audience’ was clearly silly. At the time, Nic Collins recounted the unfolding of a Connecticut concert hall performance, the klaxons growing fainter in the distance until inaudible, the audience sitting patiently in silence and then applauding when the players returned.

There are things that could be said here about the development of sound art, about the influence of Alvin Lucier, about echolocation, about bats and blindness, ships and sirens, temples and time, and those 18th century travellers in the Lake District who used cannon fire to enjoy the romantic sublime of echoes bouncing around the lakes. I think always of Giovanni di Paulo’s 15th century tempera panel, Saint John retiring to the Desert, Saint John emerging from a city gate, a small bag of possessions slung from a stick; in the centre of the painting he can be seen again at the mouth of a mountain pass, an echo of himself dwarfing the tiny buildings depicted on the plain below. This technique is known as ‘continuous narrative’. “The artist’s intention in showing the same figure more than once was clearly to indicate the passing of time,” wrote Alexander Sturgis in Telling Time.

David Toop Blog July 10, 2013

-