RE_EXHIBIT 1

Double Acts: Collaborative Partnerships in Early Artists’ Video

Curated by Chris Meigh-Andrews

Featuring:

Brian Hoey and Wendy Brown; Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield; The Duvet Bros (Peter Boyd Maclean and Rik Lander); Gabrielle Bown and Chris Meigh-Andrews.

22 September 2023 - 29 October 2023

Having been invited to identify a theme and to select some relevant examples of this approach from the Rewind collection, I have chosen to present works by artists working collaboratively. The medium of video is particularly suited to this way of working as it requires a range of skills and combines a number of distinctly separate disciplines, both technically and creatively.

The examples I have chosen demonstrate different approaches to working collaboratively, from the classical division of labour, through to creative symbiosis via dialogue. The artists in this selection explored the potential of collaborative practice to develop works which were distinctive and innovative in form and content, whilst also challenging the accepted hegemony of the creative process predominantly focused on the achievement of the individual artist.

Chris Meigh-Andrews, August 2023

Drift (1979) and Out of Sink (1981)

We met at Exeter College of Art where we were both studying Fine Art. We were in different years but ended up in the same department that was called Light/Sound at the time. Whilst our individual work took different conceptual directions, we sometimes assisted each other with practical tasks.

Our main collaborations began when we moved to London and worked at Space Structure Workshop – a group of artists working with inflatable structures and led by Maurice Agis and Peter Jones. Here we designed and built inflatable structures that we were commissioned to take to housing estates in London for children to play on – precursors of the bouncy castle but much more inventive, and would probably break health and safety regulations these days.

We became Artists in Residence to Washington New Town, Tyne and Wear, UK in 1976. This was financed by the Arts Council of Great Britain, Northern Arts (the regional arts association) and Washington Development Corporation. Originally the residency was to last for one year but was twice extended. Our brief was open, as long as we contributed to the cultural life of an emerging community. Both of us were concerned that the ability to view video art was largely restricted to people in major conurbations such as New York and London. We felt that there was a parallel between this emerging art form and the community we had moved to. We decided to mount an international exhibition – Artists Video – in order to make this available to the people of Washington. It attracted visitors from around the world and was repeated every year until 1980.

Our collaborations were very organic. On some projects one of us would take the creative lead and the other would join in the production process. On other projects we equally shared both the conceptual development and the production.

We continued making inflatables, collaborating on the design but with Wendy doing the bulk of the fabrication. In addition, Brian was developing a video installation and making video art tapes. The installation became Videvent (1975) and was shown at Video Show in 1976 at the Tate Gallery. Wendy began to become more closely involved in the production of tapes and we shortly began collaborating more closely on productions such as Drift (1979). Out of Sink (1981) was Wendy’s initiative in which she did the bulk of the shooting and Brian helped with the technical aspects of editing.

The making of the tapes did not follow an industrial model with designated roles such as Director or Editor; each of us contributed as seemed appropriate to the completion of the piece, inputting ideas in both production and post-production as well as contributing practical skills.

Living and working together can cause problems yet we like to think that our work, in a variety of media, melded our separate abilities and personalities.

Brian Hoey and Wendy Brown, 2023.

Continuum (1977-78) and The Viewer’s Receptive Capacity (1978)

Gabrielle Bown and I collaborated on three video tapes whilst we were studying in the school of film and television at the London College of Printing during the late 1970’s: Continuum (1977-78), The Viewer’s Receptive Capacity (1978) and 3:4 (1978-79). All three were made in black and white in a small television studio with input from members of the production crew.

Gabrielle and I were interested in the way that video recordings and the TV image display created new possibilities for the exploration and presentation of psychological, physical, and architectural space. All three of these tapes were attempts to try to understand and articulate ideas, concerns, and preoccupations that we shared and tried to express and investigate. We both wanted to avoid a straight-forward narrative approach, but nevertheless opted to work with sequences, duration and chronological time within the confines of the TV studio. During the two-year period that we worked collaboratively, we developed a kind of semi-scripted approach to our video pieces, preferring to work with a structured plan for each work that would provide us with a starting point but would allow for a degree of improvisation and for the incorporation of accidental events and creative serendipity, including input from other members of the production team. Across the period of our collaboration, we evolved a non-hierarchical working relationship in which we both contributed ideas, techniques and theoretical concepts which we wished to explore through our joint practice. Creative and practical decisions during the stages of script development, production and post-production were all made jointly and by consensus.

Continuum was originally intended to be a two screen-installation, with two separate video recordings played back to explore the visual and audio effect produced as they went out of synch. The existing work is thus a documentation of an intended live installation. The original recording was made with two Sony portapacks running simultaneously to produce separate recordings of a semi-scripted live dialogue. The documentation is a single channel recording of the two original tapes displayed on monitors placed side by side.

Early British video art differs from its American counterpart and British experimental film in that it is concerned less with identifying the specific properties of the medium than with analysing the conditions of viewing and the mechanics and shaping of perceptual and social space. “Continuum” is a good example of this sort of work. Originally a two-screen piece made in collaboration with Gabrielle Bown, it plays out the difficulty two lovers have in communicating with each other whilst at the same time revealing the illusoriness of the space in which their relationship is constructed. A man and a woman each occupy a tv screen. The screens are set side by side and a pendulum visible behind each of the two characters, who face each other, swings between them, first one screen then the other. The dialogue between the two is one of mutual misunderstanding and misread intentions. However, the piece ends rather humorously, with that dialogue breaking down, as both agree that the conversation need not go on in this manner as to do so would be to satisfy only what the situation of their performing the piece demands of them. Laughing, the two both rise from their seats and, if we had not already realised, we see that the space and time each of them occupies is in fact only illusorily separate, or only illusorily shared. The question is why this sort of space should be considered to be ‘illusory’ at all: why is it not real or architectural? This points to an essential difference, perhaps, between contemporary art and modern art: contemporary artists are less inclined to accept the autonomy of the art work, and consider the move of ‘revealing’ the conditions of viewing to be no less a construct than that which is thereby ‘revealed’ to be a construct. 1

The Viewer’s Receptive Capacity was a development of the previous work. We wanted to make something that was more technically ambitious and placed a greater emphasis on a direct application of some of the theories of communication we were reading. The work was also an attempt to develop a specifically televisual language, incorporating techniques and properties unique to television something we were both concerned with at the time.

The tape stretches the viewer’s patience to the limit not so much because of the media-within-media situation, but because of the two television “actors” failure to meet the basic requirements of the medium and deliver content ready for broadcasting. Like Vito Acconci’s refusal to accept the separation of production and display spaces, Meigh-Andrews here contests their split reality and argues with the woman on the monitor in real time. The struggle to maintain control over televisual production reverses the impression of real life, however, as the recorded material that creates the content of the video in return deals with the structure of television programmes. What is strengthened here in this conceptual loop, is how video can function as rupture and breakdown of television formats at the end of a chain of reception. 2

Chris Meigh-Andrews, London, 2023.

1 Jonathan Dronsfield, Short Histories of Video Art, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, 2004.

2 Yvonne Spielmann, Video Between Television and Art: Interventions into Programme Flow and Standard Formats by British Video Artists, Rewind: British Artist’s Video in the 1970’s & 1980’s, Sean Cubitt and Stephen Partridge, Eds, John Libbey Publishing, New Barnet, Herts, 2012.

Running time (1979)

The recording for this video was made in the North East of England. An artist friend was running in the landscape and we recorded this action.

Madelon was shooting this video. Then the process of editing started, which was mainly done by Elsa. Photographic stills were made from the screen by Madelon, and those were inserted into the video. The soundtrack was made by Elsa. The installation of Running Time consisted of a single channel video shown on a monitor and six linen photographs (stills from the video), size 100 x 200 cm.

The title of this video work, Running Time, refers to its duration. A figure running in the landscape, from infinity, towards and past the camera is foreshadowed by a repeating image of himself. The soundtrack, treated similarly to the image, is made from recycling loops of a heartbeat. Both image and sound progress from the unidentifiable to the recognizable.

In close relation to other works from this period, the central focus is on the pattern of lines that function as the basic building blocks of the video image, structuring visual representation in a significant way.

Split seconds (1979)

This video was made in Lavenham (Suffolk) at a friend’s house. The splitting of the wood was to make a fire in the house. The camera work was done by Madelon and the editing by Elsa. Of course, we were both present for the shooting and editing. Then we started to examine the video and made stills from the monitor screen. We placed a small monitor in front of a larger monitor and had several photos of the splitting installed around the video work.

An axe splits logs apart; the video screen and frame are split in two at the same moment. The speed of the movement is greater than that of the eye. Nine photographs made from a split second of video verify this perpetual occurrence.

In the installation Split Seconds a small monitor is placed in front of a slightly larger one, with both monitors showing the same recording of wood being chopped. The image on the small monitor includes what remains covered up in the larger image. The movements flow from one screen to the other, turning them into a whole.

Various levels of perception of reality are introduced indirectly – the perception of the human eye as well as that of the camera. The limits of these two means of perception are unrelentingly called into question: on the one hand, the human eye, which is unable to register each movement; on the other, that of the camera, which, with its limited scope of perception – the frame – turns out to have a much smaller range than the human eye. Split up as they are, they complement each other.

The play on words implied by the title, Split Seconds, refers to the wood being split, to the image being split up, and ultimately also to perception being split.

Madelon Hooykaas, 2023

Open the Box (1986), Strickly Trigalig (1986)

I first met Rik in 1981 at The Minories Art Gallery in Colchester, Essex, where I was setting up the Film Makers’ Workshop. Rik came to see me about a super-8 camera and joined the workshop to make super-8 films. By 1983/84 I was at St Martins School of Art doing a Fine Art Film degree, and Rik was fresh out of Ravensbourne College where he’d studied television engineering. He was working at a documentary production company called Diverse and had access to broadcast quality equipment, plus a massive library of news footage, old adverts, and films. I spotted a flyer at college looking for work to be shown on a mound of TVs in the top room of the Fridge Club in Brixton.

I approached Rik to collaborate on a multi-screen show for the Fridge, and that was the start of us working together as the Duvet Brothers. Rik had keys to Diverse and knew the alarm code. After college I’d meet him in the pub across the road from Diverse – we would have a couple of beers until everyone had left. We’d work all night and then clear the place of smoke and beer cans and get out before anyone arrived. Rik would go to the local cafe then go back to work for a shift.

We worked well together initially because we were coming from two different creative backgrounds. At college I was experimenting with creating abstract shapes and colours by crash zooming in and out on flowers and whip panning, then slowing them down to blurry colourful shapes. This was motivated by people from the painting department coming to make films, so I thought, why not see if I can use film as a painting medium? Rik was interested in ways of exploiting the creative potential of all that kit; rewiring behind the racks to create feedback. We complemented and inspired each other. “What if we try this…” Multiple layers of video, blurry whip pans, archive footage, treating the edit controller like a drum machine and, of course, the repeat edit. These were the ingredients of what was labelled at the time, Scratch Video.

There were often 3 or 4 machines playing and a lot of bouncing and tape changing. We’d get a camera out and pan past the monitor in the dark, then multi-layer that. Many times, he would get a paper and pen out to plan the number of mixes and effects as it got very complicated at times. We created that rare space where we were both free to play and innovate.

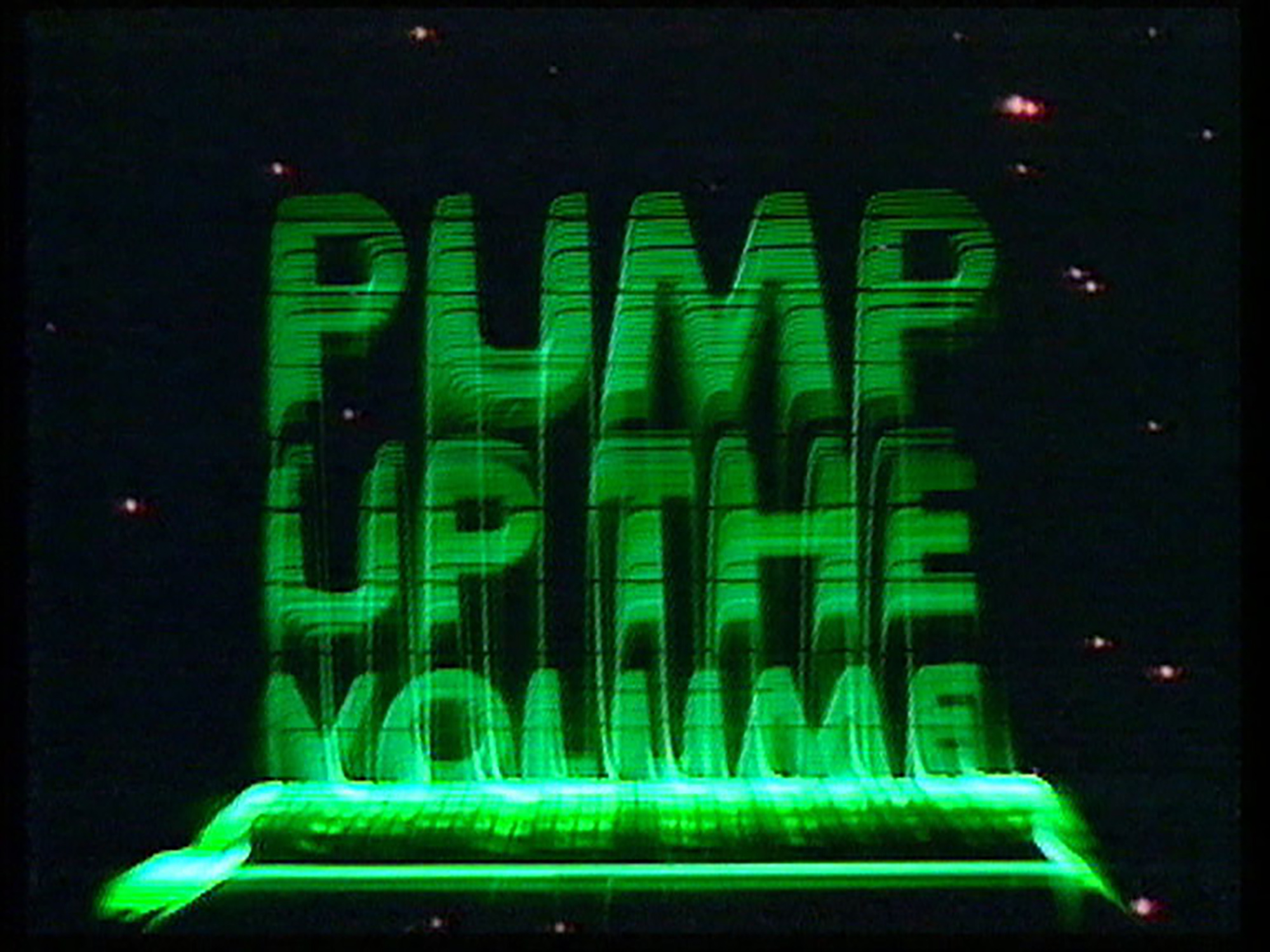

We are best known for our archive based Blue Monday and MARRS Pump up the Volume, but our experimental shooting and editing style is visible in promos for William Orbit’s Torch Song, Colourbox and Blue in Heaven. We made the title sequence for the TV series about TV, Open the Box. After the Fridge show, we continued doing live multi-screen shows. Strickly Trigalig was part of the show, an abstracted moving painting.

Peter Boyd-Maclean, 2023

There was a time when collaborations between artists were not as welcome or as well thought of as they are now. For example, when Gabrielle Bown and I were considering post graduate study at the end of the 1970’s, we were advised not to make joint applications or to rely on the work we had made together as evidence of our creative practice. We were told that there would be an assumption that only one of us was responsible for the work and the other was simply “tagging along”. In fact, we were informed there was a derogatory term for this kind of approach- dubbed the “Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum Syndrome”.

But working collaboratively was often a practical necessity when using moving image technology in the 1970’s, even if recent advances had made it easier to produce video without the kinds of crews that were the norm in more traditional film and television production. Creatively I had found this way of working both valuable and beneficial and was interested to understand how other collaborative partnerships between artists working with the new medium had evolved and to learn more about their working practices and approach to the division of labour and the creative process. As a historian of the medium with a particular interest in the development of artists’ video in the UK, I was aware of the work of some of the collaborative partnerships and the Rewind exhibition has given me a chance to celebrate some of them. This on-line exhibition, the first of a series initiated by Rewind, features works in the collection by artists who have formed collaborative partnerships to develop works that demonstrate a diversity of approach and aesthetic sensibility, each an example of the range and potential of the video medium.

My collaborative works.

Gabrielle Bown, (who sadly passed away some years ago) and I worked together on 4 video pieces between 1977 and 1979. The first was an exercise made early in the 2nd year in response to a brief on the theme of “Space”, this was followed by “Continuum” made later the same year. In VRC we tried to extend the creative dialogue we had evolved with the first two pieces to include the structure of the work, so that form of the work itself was a kind of dialogue, both between ourselves on screen and with the rest of the production crew. This process was something we had begun to consider and explore with “Continuum” that we attempted to extend and refine in “The Viewer’s Receptive Capacity”, with limited success. I am sure that this was at least partly due to my limitations as an “actor/performer”.

The crew were all fellow students in the 2nd year of the Film & TV course at the LCP, that were sympathetic to what we were attempting to do. We deliberately chose to cast Ken Mc Mullen (who was one of our tutors) as the floor manager because we knew he would be disruptive in some way and we hoped we might be able to harness or incorporate this within the piece.

Chris Meigh-Andrews, October 2023.