RE_EXHIBIT 5 HOUSEWATCH REVISITED:

Inside the House

Curated by Carmen Mateo

“Taking film outside the cinema and gallery reminds me of its roots in the fairground booth. In Britain today, the need to brighten up our streets (in this case literally) is not simply an artistic demand but a social one too.”

Michael O’Pray, Art Monthly, No.92 Dec/Jan 1985/86

The exploration of urban space, cinema, and performance was central to the work of the HOUSEWATCH collective in the 1980s and 1990s. Inspired by the desire to move beyond traditional gallery and cinema settings, the group’s groundbreaking projects reimagined the relationship between art, space, and audience. HOUSEWATCH transcends the boundaries of cinema and public art by integrating light, film, sound, and live performance into everyday, often overlooked, urban environments. This exhibition showcases key works by artists Ian Bourn, Lulu Quinn, George Saxon, Tony Sinden, Stanford Steele, Chris White and Alison Winckle, who each sought to engage the public in new and immersive ways.

The collective’s innovative approach to blending art with the fabric of everyday life continues to inspire contemporary practices. Their legacy lives on as a testament to the transformative potential of art in public spaces, where the boundaries between audience, environment, and performance are fluid and ever-evolving.

Acknowledgements: This exhibition develops from materials and interviews collected from the REWIND archive and Ian Bourn interviews. Texts by Carmen Mateo and Ian Bourn.

Carmen Mateo Guerra is a recent MFA Curatorial Practice graduate at the University of Dundee, she specialises in research-based approaches to contemporary art and culture. Her work focuses on presenting alternative narratives through curatorial projects oriented around social involvement, community, and connectivity. Carmen supports artist development in expansive ways, encouraging the creation of works in various art forms such as sound, photography, film, and writing. She actively collaborates with both emerging and established artists, as well as organisations, to facilitate the creation of new works tailored for diverse settings, including galleries, digital platforms, and festivals.

HOUSEWATCH was a pioneering artist collective that redefined the relationship between film, architecture, and performance through immersive, site-specific installations. Emerging in the late 20th century, their work spanned a range of experimental formats, from large-scale projections on buildings to mobile structures and interactive performances. Projects like Little Big Horn and Contra-Flow explored the visual potential of cars as moving screens, while Paperhouse and Imaginary Opera in Japan pushed the boundaries of projection mapping, using innovative technology to transform spaces into cinematic environments.

By shifting experimental film practice beyond traditional venues, HOUSEWATCH blurred the boundaries between private and public space, expanding the language of visual storytelling. Their installations engaged directly with the rhythm of city life, using elements like bicycles, cars, and even entire buildings as vehicles for artistic expression. They invited audiences to become active participants rather than passive observers. HOUSEWATCH’s radical approach not only challenged conventional spectatorship but also left a lasting mark on contemporary media art, redefining how moving images interact with the built environment.

The first HOUSEWATCH project emerged from Ian Bourn’s vision of transforming a domestic house into a multi-screen cinematic experience, projecting films across its windows and to engage both architecture and audience in a new way

Recognising the logistics, financial challenges and personnel needed for creating multi-screen film compositions and converting the street-facing windows of a house into projection screens, Bourn realised that collaboration was essential. So, he put together a group who would both make the films and act as technicians and projectionists on the night.

The original HOUSEWATCH collective consisted of Tony Sinden, an experienced film installation artist who had met Bourn when both exhibited in the 1979 Hayward Annual, George Saxon, who’d studied with Bourn at the RCA and whose film Another Window (1984) aligned thematically with the project’s concept, Lulu Quinn, an artist with prior experience in expanded cinema and site-specific projects and Alison Winkle, whose experimental films included a piece using projection onto curtains Bourn had seen at the Serpentine Gallery in 1984. The final member of the group, Chris White, was an artist/neighbor embarking on his first moving image project and who’d allowed his own house to be used as a ‘warm space and canteen’ for audiences of the show.

It was decided that each artist create a multi-projection work of between 5 to 10 minutes duration, that temporarily transformed the building and responded directly to its architectural style and the surrounding environment. The result would be a programme of six distinct works, each a very different interpretation of the ‘house’, for a show lasting approximately one hour.

Alison Winkle, for example, based her piece on Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), focusing specifically on Jane’s incarceration and when the house in Fairfield Hall burns down, with raging flames filling the windows. By contrast, Chris White’s work turned the house into an aquarium, with the artist performing as frogman, and swimming from room to room. Reflecting the diversity of approach to filmmaking practice, Lulu Quinn’s composition used more conceptual methodology, with arrangements of fragmented text appearing across the windows and with a soundtrack of building regulations being read out.

Unlike traditional exhibitions, a HOUSEWATCH installation would blend seamlessly into its surroundings until nightfall, when the ordinary house would suddenly transform, room lights remaining off while moving images flickered through the windows. The building itself took on a new personality, becoming an enigmatic presence within the urban landscape. The unexpected nature of the experience was key, the passersby would stumble upon it by chance, finding something they had not sought out.

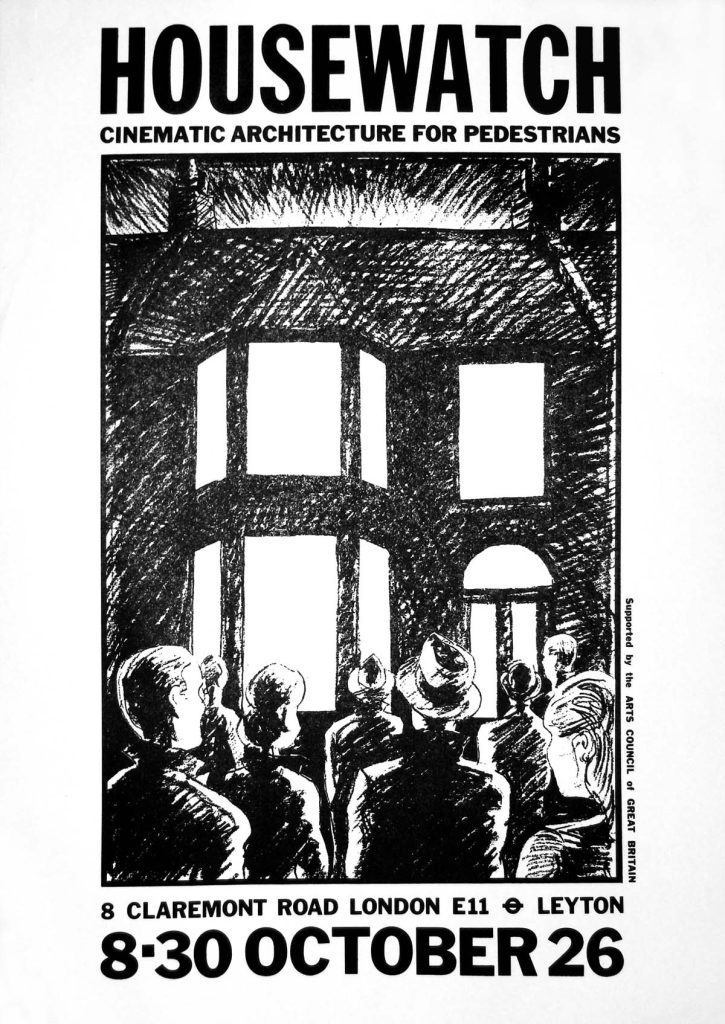

The first presentation by the group, using Bourn’s own house in East London in October 1985, attracted huge interest from the public and press, including articles in The Times and coverage on BBC2’s Newsnight.

The central theme of HOUSEWATCH’s Wounded Knee (1990) was to question political and environmental notions of ‘transport and road building’ versus ‘homes and housing’ as it was sited in a street due for demolition and in a residential community living under threat from a motorway building scheme. It was shown in East London as part of The Whitechapel Open Studios Programme 1990.

It was an experiment in expanding the HOUSEWATCH concept, using two separate buildings in the same street and two parked motor vehicles, each allocated to individual members of the group. It replaced the original film-programme format with a more open-ended approach, treating the houses and cars as part of a wider installation, with each individual artist’s idea physically separate, yet in interaction with each other. Pre-programmed slide projection and film loops were used, making the event continuous.

Inside one of the house installations, hidden from the audience, a group of musicians improvised a live soundtrack for the moving images on its windows. Wounded Knee used recorded sound and ‘live’ music, car horns, engine noises and incorporated the flickering lit windows and rhythmic rattle of nearby passing tube trains, audible and visible from the street.

Ian Bourn’s house windows were filled with crawling maggots and images of an open mouth coughing up cockroaches, whilst Sinden’s parked car had ghostly projected window wipers, and those approaching it were made ‘damp’ by a hidden spray coming over a garden wall. Another house was revealed to have a ‘combustion engine’ interior. The combination of such elements created a layered effect, making windows appear both transparent and opaque at different moments, the diverse components at times confrontational, at others in harmony, and simultaneously engaging viewers with the precarious state of the surrounding community.

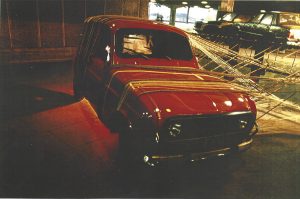

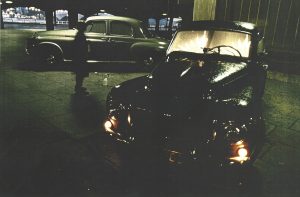

Taking place at the South Bank Centre in June of 1992 and situated in the ‘Undercroft’ space below the Queen Elizabeth hall, Little Big Horn featured a new series of individual installation pieces, with each artist working on a particular choice of vehicle/s to create an ‘underground car park’ environment.

Following on from ideas first developed in Wounded Knee (1990), the HOUSEWATCH group produced a mixed-media event made-up of individual cars and car groupings, expressing various approaches to the automotive theme; from scenarios presenting cars as sculptural objects — to situations reflecting the personal obsessions of the artists or the concept of cars more generally as contemporary cultural icons.

Bourn’s piece used a black Ford Capri, its projected ‘occupants’ dressed in fetish gear, to explore the idea of car-sex in the era of Aids. George Saxon positioned two cars in a ‘permanent collision’ scenario, with drivers and passengers being thrown about inside. If one peered through the windows of Lulu Quinn’s muddy old Morris Minor van, illuminated eggs on a bed of straw seemed about to hatch.

With nine vehicles in total, each emitting its own soundtrack; a mix of thumping mega-bass disco music, screeching brakes, crashing metal and glass, opera music wafting from a breakdown van and chicken noises, the Little Big Horn installation, at moments of combined intensity, created the mechanical/musical atmosphere of an insane funfair. The piece ran for a week and, because of its shadowed location, could operate in both the daylight hours and after dark.

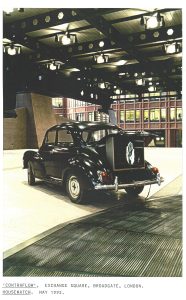

Contra-Flow was a live performance event (with evening projections) that took place in Broadgate’s Exchange Square near London’s Liverpool Street station.

Contra-Flow was to be HOUSEWATCH’s first complete collaboration, with all six artists working as a team and improvising on a single concept and performance.

As with many of HOUSEWATCH’s projects, Contra-Flow challenged conventional spectatorship and questioned the passive viewing experience associated with traditional cinema or theatre. Instead of formal screening arrangements and designated arenas for art practice, images, sounds and actions unfolded within the environment itself, requiring those encountering it to navigate and move through the changing layout and aspects of the performance.

The event saw 18 dilapidated Morris Minor cars shipped into what is a pedestrian area and pushed around by the six artists of HOUSEWATCH over a five-day period. One by one the cars were moved into different positions, arriving at new arrangements and configurations. These choreographed actions were performed ‘workman-like’, with the artists in boiler suits as if working to a curious and never-revealed agenda. The performances often took place during rush hour and lunch breaks, as white-collar workers passed through on their way to city office jobs, to the annoyance of some and the intrigue of others.

The cars were pushed along carefully devised zig-zag routes through the pedestrian space, creating a dynamic interaction between movement, light, sound, and architectural surroundings.

Taking place at a scheduled time each evening, a row of 24 film projections appeared on the windows across one floor of a tall office block overlooking the square. These created the impression of a never-ending line of Morris Minors being pushed across from left to right.

Functioning like a fragmented soundtrack to events, intermittent snatches of Andy Williams singing his hit ‘Almost There’ were heard. On one evening, a crooner in the square sang the song live and performed a duet with an opera singer situated on a high fire escape near the car projections.

Although largely ambiguous in tone, Contra-Flow could also be interpreted as openly humorous and full of irony, depicting and celebrating the car at its most meaningless; when the engine doesn’t work and it has to be pushed. Taking place at the start of May, it also invited readings of the piece as a variation on Morris Dancing.

The event’s success further cemented HOUSEWATCH’s reputation as pioneers of urban cinematic interventions, bridging the gap between experimental film, performance art, and the built environment.

In 1986 Artangel presented a version of Cinematic Architecture for Pedestrians for a short tour of three different London venues, using houses in Spitalfields, Chelsea and Bloomsbury (next to the British Museum).

Interest in HOUSEWATCH events gathered pace after TV coverage and accounts in national newspapers, and a false perception grew that the group were like a pop band (i.e. with tour bus and able to deploy at a moment’s notice). The reality was far from it. There was no fixed management hierarchy. With each artist’s work being the chief consideration, group decisions were made along completely democratic lines. Financial and logistical constraints meant that each future show required careful planning well in advance.

In 1987 the Scottish Arts Council invited the collective to create a project using the Assembly Rooms venue in Edinburgh. Although some of the film material devised for terraced domestic architecture seemed usable, new works had to be made that both responded to the character of the local architecture and be designed to fit completely different window dimensions. It took a year’s preparation to realise the project, including trips by artists to the site, and the creation five specifically designed multi-screen films. By this time, HOUSEWATCH consisted of five artists, with Chris White having left to pursue his painting career.

In 1988 there followed two incarnations of the ‘Cinematic Architecture’ format, as part of the Bath and Brighton Festivals. Like previous work, sensitivity to site and surrounding environment were paramount. Most of the individual contributions were bespoke creations and personal responses to each new viewing situation.

The opportunity to take HOUSEWATCH to Japan arose in 1991, when a music festival director, Yutaka Fujishima, having heard about HOUSEWATCH’s activities, managed to track down the group by contacting the London Film Makers Co-op, where George Saxon was working at the time. Mr. Fuijishima invited HOUSEWATCH to participate in the Contemporary Music Forum of Kyoto, an experimental music festival seeking to expand boundaries, incorporating visual ideas and links to conceptual art (as in works by composers like John Cage and so on).

To present HOUSEWATCH so far away, the team faced significant challenges regarding each member scouting locations and tailoring their work to specific buildings within Japan’s unfamiliar architectural landscape. It was decided that Ian Bourn should travel to Japan in 1991 on a research trip, documenting possible architectural venues and sites, and recording extensive video footage for the whole group to study.

1992 proved to be the most intensive period of creativity and achievement for HOUSEWATCH, with Bourn organising the group’s tour of three Japanese cities (Kobe, Kyoto and Mito) and Tony Sinden and Lulu Quinn liaising with the Southbank and Broadgate Events, for two major London shows (Little Big Horn and Contra-Flow). This set the pattern for how the group approached new projects, with members assigned different roles in the administration, publicity and technical requirements pertinent to each new situation as it arose. HOUSEWATCH now comprised of six members again, with sculptor and mixed media artist Stanford Steele joining the collective in 1991.

“What is significant about Housewatch is not the reality of the contents of their films but the new methods of projection they use, and the fact that they are searching for a more direct, newer way of contact with society”

Nakamura Keiji, ‘Remix’, 4th International Contemporary Music Forum of Kyoto catalogue, 1992

For presenting HOUSEWATCH in Japan, due to financial restraints, only one member of the group was able to conduct a research trip. Ian Bourn travelled in 1991 and, with Yutaka Fujishima, the Japanese curator/host, drew up plans for a tour of three Japanese cities.

After much discussion and having viewed the research material, the group came up with two project proposals, each able to address any problems that might arise regarding site-specificity and the artists’ ability to respond to unfamiliar architecture in a different cultural setting.

The first idea was to select a Japanese building that already looked familiar, such as those built in a European style. This became the basis of the Imaginary Opera (1992), which used the Kyoto Prefectural Museum building, being similar in style to British municipal architecture of the Victorian period.

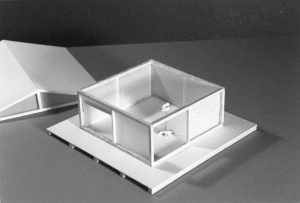

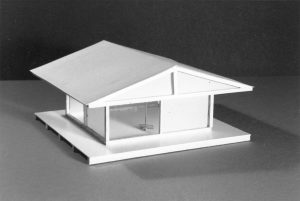

The second proposal was to construct a specially made building, designed by the group, yet based on a Japanese model and made using traditional materials and construction methods. The advantage of having a prefabricated structure, meant it could easily be reassembled and moved to different sites. In this way the artists could easily visualise how their work would look to audiences in Japan and the architectural context in which it would be framed. This became Paperhouse (1992), an innovative multimedia installation idea, marking the collective’s first major venture into video projection.

A rough design was drawn up, based on a simplified version of a traditional Japanese teahouse, to be made from wood, with rice paper screen walls that would be ideal for projection purposes. It was square in shape with video projectors housed within, so that video imagery could be viewed on all four sides. It was constructed in Japan by a local team using traditional materials and carpentry.

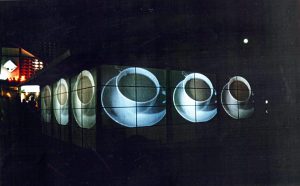

Appearing on a street corner in Mito, Paperhouse’s unassuming appearance led passers-by to mistake it for a kiosk or temporary shop, only to be surprised when its surfaces came alive with video projections.

Similar to the original London shows, each of the six HOUSEWATCH artists made a multi-screen video work to fit the structure, so that the Paperhouse could undergo six transformations in a programme lasting approximately one hour.

In Tony Sinden’s piece, the screen-walls became geometric patterns of water ripples and rushing streams, whilst in Lulu Quinn’s, winds blew leaves and steam wafted from large hot cups of English tea. Stanford Steele’s work filled the screens with piled high tree logs, Ian Bourn had 12 versions of himself dancing around the structure and Alison Winckle made its walls into glass, across which huge mollusks slowly trailed. George Saxon turned Paperhouse into a water-filled tank, in which a giant pajama-clad boy tossed and turned, his body taking up the whole interior, head at one end and feet at the other.

Paperhouse (1992) was built and tested, with tech support and equipment from Sharp Corporation, at Xebec Hall, Kobe, where it received its public premiere. The piece then travelled to Mito (supported by Art Tower Mito art gallery), and finally was exhibited in the Prefectural Museum, Kyoto.

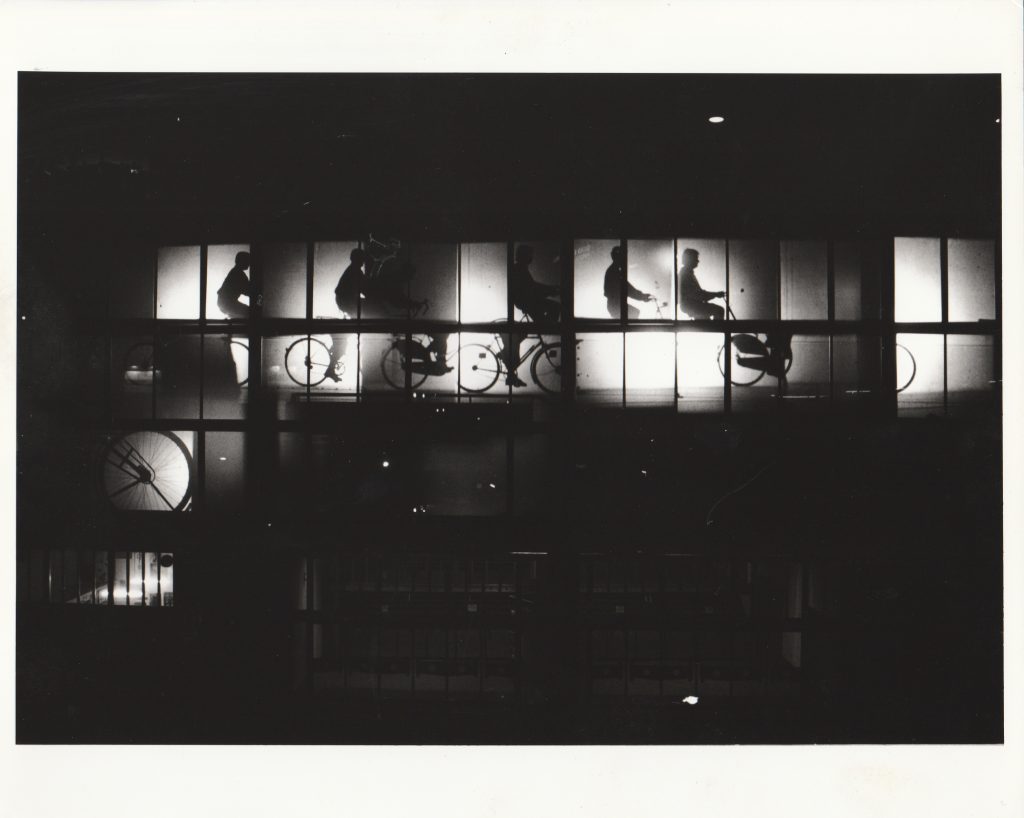

For HOUSEWATCH projects in Japan, in addition to the touring Paperhouse video installation, the group also staged Imaginary Opera (1992), a 35-minute mixed media performance event featuring bicycles, film projections and a live orchestra at Kyoto’s Prefecture Museum.

Developed as part of their ongoing interest in urban transport and the environment, this time using bicycles instead of motor vehicles, the work employed multiple film and slide projectors to illuminate the windows of the building, with silhouettes of the artists as cyclists continually moving through its street-facing façade.

Part of the group’s involvement in The International Contemporary Music Forum of Kyoto, was the opportunity to make work responding to the music of the then emerging modern British composer Steve Martland (1954 – 2013). His newly composed Crossing the Border (1991) was used as the soundtrack to Imaginary Opera and, like Contra-Flow shown earlier the same year, saw all members of HOUSEWATCH collaborating on a single film and performance artwork.

Martland himself was intended to conduct music’s premiere in Japan but, due to other commitments, could not make the trip, so it was performed by an ensemble of Japanese musicians.

“Looking from the street, there were projections on the windows of the Museum, creating the illusion of cyclists travelling through the building. The audience was invited to enter the Museum, where the orchestra was playing, surrounded by moving projections and shadows… During the event we rode and pushed bicycles, both inside the building and outside in the streets of Kyoto; crossing the frame line that separates film from its surroundings, where the edges are less defined, where the audience is part of the environment.

The music Crossing the Border has distinct sections with changes of mood and tempo. Rather than interpret the different parts with illustrative sequences of film, we chose to use the same images throughout, as projected ‘loops’ of film of different lengths. In this way an endless variety of rhythms is created that ‘drift’ in and out of sync with each other and the tempo of the music – in fact it is left to the audience to make the relationship of matching image to sound.”

Tony Sinden

Imaginary Opera was restaged in 1994 at London’s Southbank Centre, to open its Meltdown Festival. That year the Festival celebrated Dutch composer Louis Andriessen, whom Martland had trained under, so this time he and his musicians were able to provide the live soundtrack as originally intended.

The side windows of the Royal Festival Hall, facing the Hayward Gallery, provided the glass for back-projection and the production used over 40 cine, film and slide projectors. The audience participation element was further enhanced by allowing people to enter the building and see the band playing, and to walk in front of light-beams from a row of projectors positioned on a first-floor walkway. Thus, the shadows of those walking through, mixed with, and were indistinguishable from, the projected silhouettes of the cyclist/artists.

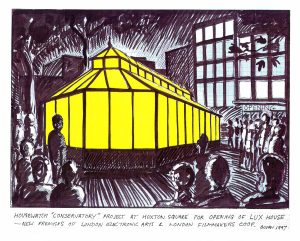

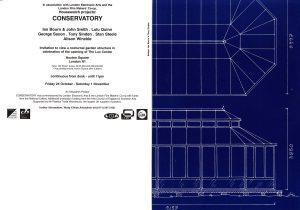

The Conservatory video installation was shown in 1997 and commissioned to celebrate the opening of the Lux Centre in Hoxton Square London

“…Now well established as one of the UK’s most intriguing sound and vision innovators, Housewatch started out using film projections to transform houses into multi-faceted installations. Some ten years on, Housewatch are using high-definition video projection and, for this project a UPVC structure called Conservatory. As ever, Housewatch are in pursuit of an art form that is accessible, public and experimental.”

Nick Houghton, Artists Newsletter, Jan 98

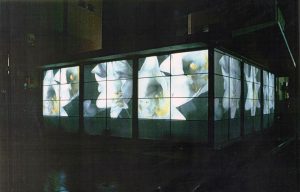

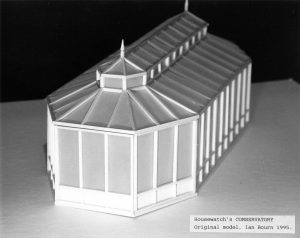

After the success of their Japan shows, particularly the 12-screen video compositions created for Paperhouse (1992), HOUSEWATCH wanted to create similar works for an outdoor structure in the UK which, like Paperhouse, could be viewed on all sides, but would not look ‘out of place’ in a British setting.

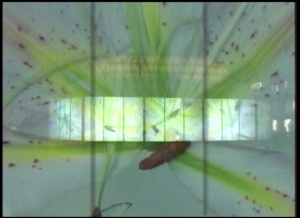

Modelled on a freestanding Victorian design, Conservatory was a 15-metre-long structure that housed an internal arrangement of 12 projectors, enabling video projection onto its ‘screened glass panes’ (actually translucent acrylic). This allowed audiences to view continuous moving imagery across the exterior and on all sides. Conservatory was also designed so that it could be transported and reassembled at different sites, specifically parks or garden spaces and so that it could potentially tour the UK and beyond. The idea was suggested from a model made by Ian Bourn and the design was developed and drawn up by Stanford Steele.

Situated in the tree-lined square, audiences saw the greenhouse structure go through a series of audiovisual transformations created by each of the HOUSEWATCH artists in turn, in a programme of works lasting just under an hour.

“…With six distinct pieces on show, the programme ranged from George Saxon’s sinister A Place for Tender Things, to the striking simplicity of The Kiss by Ian Bourn and John Smith. In the former, technology impacts with mythology in the creation of a monster man who writhes across the overlapping screens of the conservatory. It is a dark and unsettling piece, which offers a warning (perhaps) of the digital dreams we aspire to. In The Kiss a hothouse flower seems to twitch and twist until at the very last moment it is destroyed. This is a short, yet resonant piece, and one hopes for further collaborations between Bourn and Smith.

Similarly powerful is Tony Sinden’s Heart of Glass. Here Sinden evokes the power and beauty of water in motion. At times almost abstract, the piece is made all the more intriguing by a closing sequence that twists our notions of ‘natural laws’…”

Nick Houghton

NOTE: Filmmaker artist John Smith, who collaborated with Ian Bourn for Conservatory, had always contributed to HOUSEWATCH projects over the years. He was cinematographer on both Contra-Flow and Imaginary Opera in 1992, on projects where all members of the group were performers in front of camera, and famously he filmed the maggots for Bourn’s piece in Wounded Knee (1990).

Tony Sinden died in 2009.

References:

Bourn, I. & Warwick, M. (2007), Interview of Ian Bourn REWIND Archives. University of Dundee.

Sinden, T & Warwick, M. (2007) Interview of Tony Sinden REWIND Archives. University of Dundee.

Bourn, I. (2024), Phone Interview with the author, [3 December].

The Guardian & Gazette Newspaper (1985), November 8 Edition.

Performance Magazine (1985), Oct/Nov Issue, No. 37.

The Times (1985), Monday Edition, November.